Ship Quality Products Faster, With Less Risk

Delivering the highest quality possible can be a challenge as release cycles get shorter and shorter. If you lack visibility and alignment around requirements and testing, you’re putting quality, safety, compliance, and your brand reputation at risk.

Perforce ALM provides a single tool to centralize, map, and manage all development artifacts across the entire lifecycle with complete traceability. Plus, it's ISO 26262 certified to meet the most stringent functional safety requirements. Streamline your processes and get to market on time — without compromising quality or safety.

What makes Perforce ALM one of the best ALM tools?

Key Benefits of Perforce ALM

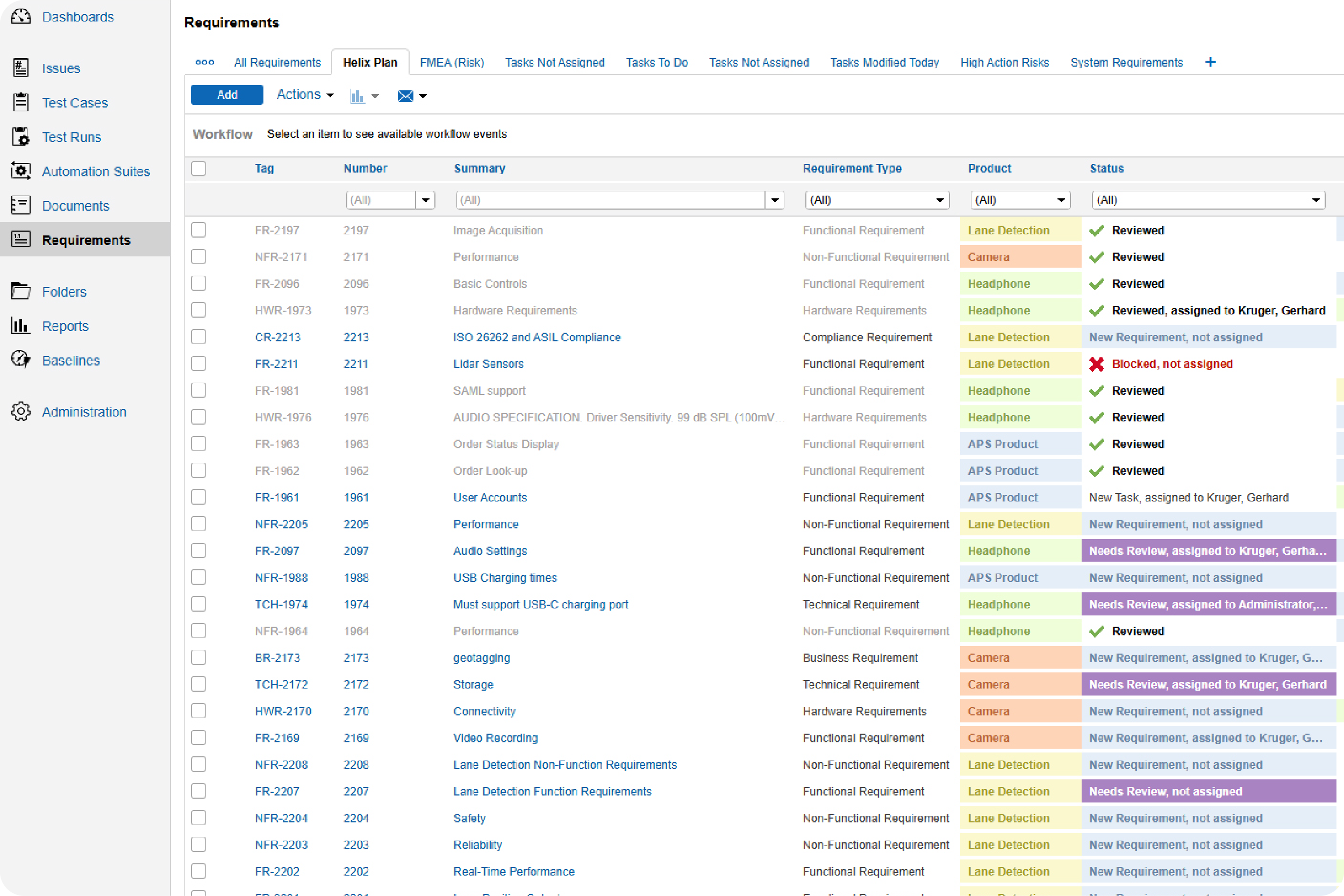

Keep everyone up-to-date on the latest requirements.

Perforce ALM makes it easy to create requirements and share requirements documents. You can do requirements reviews and get approvals within the solution. Plus, you can easily reuse requirements across projects. Watch the 20-minute demo to see it in action.

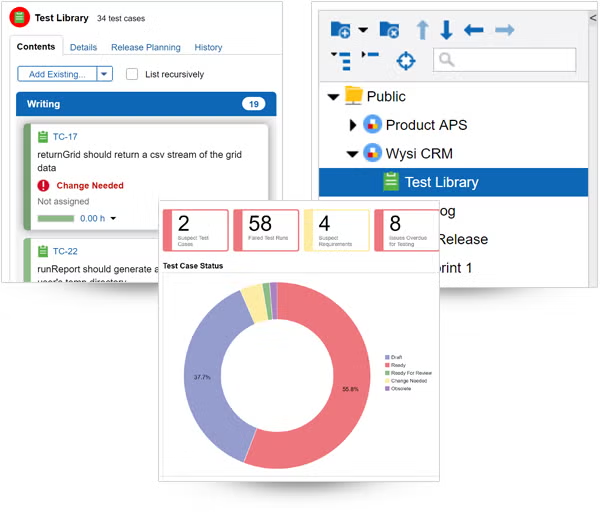

Make sure your test cases are approved and check in on the status of your test runs.

With Perforce ALM, you can create test cases based on requirements. Generate test runs based on those test cases. And trace test results back to requirements. You’ll rest assured that your product has been thoroughly tested — before it hits the market. See for yourself in our 20-minute demo.

Find and resolve bugs — before your product ships.

Tracking bugs is easy in Perforce ALM. If a test run fails, ALM will automatically create an issue. And you’ll be able to track that issue through to resolution. So, you’ll be confident you’re shipping the best possible product — instead of waiting in fear of customer-reported bugs. See how it works.

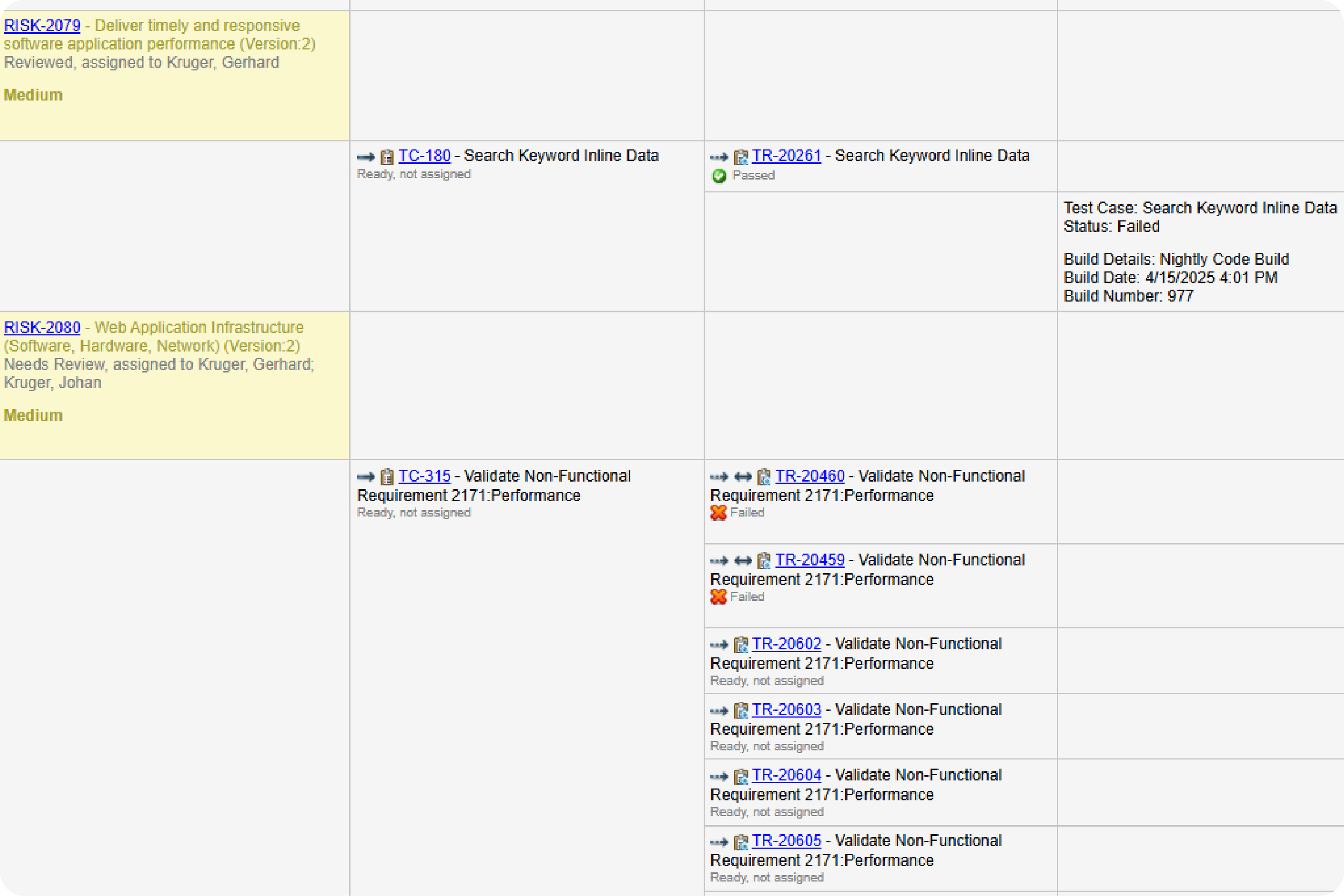

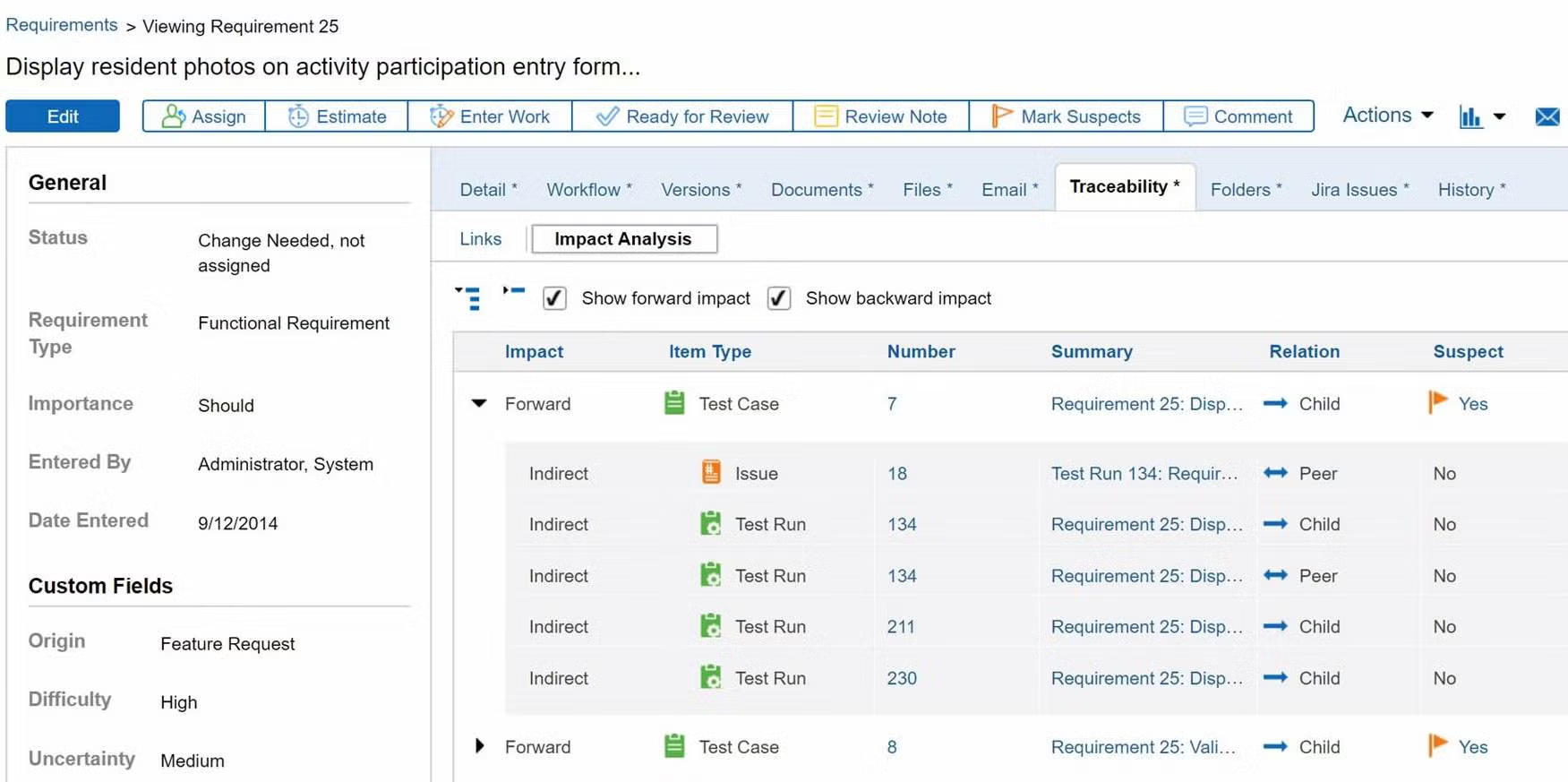

Prove compliance by creating a traceability matrix.

You don’t need to manually create a trace matrix in Perforce ALM. Requirements, test cases, and issues are linked, so traceability happens automatically. From there, creating a traceability matrix is a snap. You can also compare historical data with baselines. You’ll be able to prove compliance in record time. Create your own traceability matrix for free.

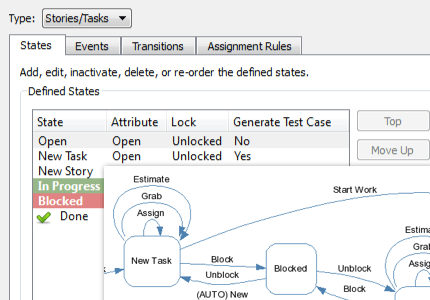

Be more productive with automated workflows.

Perforce ALM is all you need to improve your development workflows. Simply let the workflow engine handle states, events, transitions, assignment rules, escalation rules, triggers, and more. You won’t have to manually track them. Learn more in our free demo.

Manage risk — before it impacts your bottom line.

With Perforce ALM, you can create requirements based on risk. You can also do risk analysis, including FMEA and impact analyses. And you can quickly create a traceability matrix to prove compliance. Watch the 20-minute demo to see how easy it is.

Deliver the metrics that matter.

Your development team needs to measure progress to make sure your release is on schedule. Perforce ALM’s reports give you the information you need to make timely, data-driven decisions. Whether you need to know impact, burn down rates, project progress, or productivity, this ALM tool has you covered. See reporting in action.

Gain a single source of truth by integrating your ALM tool with your existing tools.

Perforce ALM easily fits in with the rest of your development toolset. It comes with out-of-the-box integrations to Jira , Jenkins, and Helix Core, among others. It also integrates with collaboration tools, including Slack. And it offers a REST API to connect any other tool you have. Learn more about integrations in our free demo.

See What Our Customers Think About ALM

91%

Improves alignment around requirements and changes.

92%

Improves traceability throughout our development process.

100%

saw a return on their investment within two years.

80%

Brings consistency & clarity to our development process.

70%

Improves our confidence in product releases.

*Sources: G2 Spring 2025 Awards and customer survey of 90 users of Perforce ALM, June 2024.

See How Perforce ALM Delivers Traceability

What can Perforce ALM do for you? Manage requirements. Tests. And issues. All in one spot.

Integrate with Your Existing Tools

Add traceability to Jira, trigger automated test runs in Jenkins, and more thanks to off-the-shelf integrations with leading development tools.

All Integrations

See How it Works

See for yourself how Perforce ALM automates traceability across the entire product lifecycle.

Try Perforce ALM Today

Try ALM free for 30 days. You’ll see for yourself how easy it can be to manage requirements, run tests, and track bugs — all from one ALM tool.